I HAVE BEEN CURIOUS to unite two contemporaries whose characters and destinies couldn’t be more different, and to take a closer look behind the most common perceptions and associations with them. Niccolo Paganini (1782-1840) was the living legend, a celebrity who revolutionised the violin. Franz Schubert (1797-1828) was a modest genius, achieving little recognition in his lifetime and yet is now acknowledged, amongst many other things, as the greatest song composer of all time, who dramatised hundreds of poems into most compelling musical storytelling. What – and whom – motivated and influenced their contributions to the violin repertoire?

Opera was the great popular form of the age, and some of the composers the international superstars. The most prominent of these was Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) , who was in a class of his own. Schubert was in awe of Rossini’s talent, stating in a letter that “You cannot deny him extraordinary genius”. Paganini, although being a fully-fledged composer in his own right, based several of his dizzying show pieces on themes from popular operas and ballets; the two most well-known of these being variations on arias from Rossini’s Mosé in Egitto and Tancredi ( Di Tanti Palpiti ).

Giovanni Paisiello (1740-1816) was another famous opera composer at the time. His opera La Molinara or The Miller Maid premiered in 1788, a year after the premiere of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, and it quickly became a hit in Europe. Like Don Giovanni, La Molinara was based on an old folk tale, and its plot inspired librettists, poets and writers. Amongst them was Wilhelm Müller, whose poems Schubert turned into the song cycle Die Schöne Müllerin.

One of my own personal, favourite themes ever since my childhood is Nel Cor Piu Non Mi Sento, a love duet from the second act of La Molinara, which theme served as inspiration for numerous composers. Most famously, Beethoven wrote a set of Molinara-Variations for piano, after having heard the opera. Schubert also included elements from Nel cor piu non mi sento in the lied Im Dorfe from his song cycle Die Winterreise. And, of course, Paganini ‘dramatised’ it on the violin.

Schubert, himself an able violinist, raved about Paganini’s playing – “In his Adagio I have heard an angel sing!”, he exclaimed to a friend. Upon the violin phenomenon’s much anticipated visit to Vienna in 1828, Schubert was gripped with Paganini fever, and he managed to afford tickets to Paganini’s concert thanks to a rare concert engagement he had himself on the day prior, and spent a large chunk of his fee inviting along his friend: “I tell you, you have to come-you shall never see the fellow’s like again. And I have stacks of money now, so come on!”

His inspiration by virtuosity was proven in two monumental works for piano and violin written in 1826-27. The first one is almost obsessive: a ridden, visionary Rondo Brilliant. The second is the grand Fantasie in C major. At its heart is a set of variations on Schubert’s famous Lied Sei mir gegrüßt.

Both pieces were premiered by their dedicatee, an aspiring virtuoso who also happened to be Schubert’s own student in composition. The violin prodigy Josef Slavik (1806-33) had excited a great sensation in Vienna and was widely expected to become Paganini’s successor. Frederic Chopin who met and heard Slavik on several occasions, described his skills thus: “With the exception of Paganini, I have never heard a player like him. Ninety-six staccatos in one bow! It is almost incredible! He plays like a second Paganini, but a rejuvenated one, who will perhaps in time surpass the first. Slavik fascinates the listener and brings tears into his eyes... he makes humans weep, more he makes tigers weep.”

Slavik’s life, however, was cut short by illness and he died aged only 27. It turned out to be Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst (1812-65) who would carry the torch as Paganini’s successor and leave a legacy behind for violinists at the highest technical level - although not quite at the scale of Franz Liszt (1811-86) , Ernst’s Polyphonic Studies for violin are equivalent to Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes for piano in technical demand.

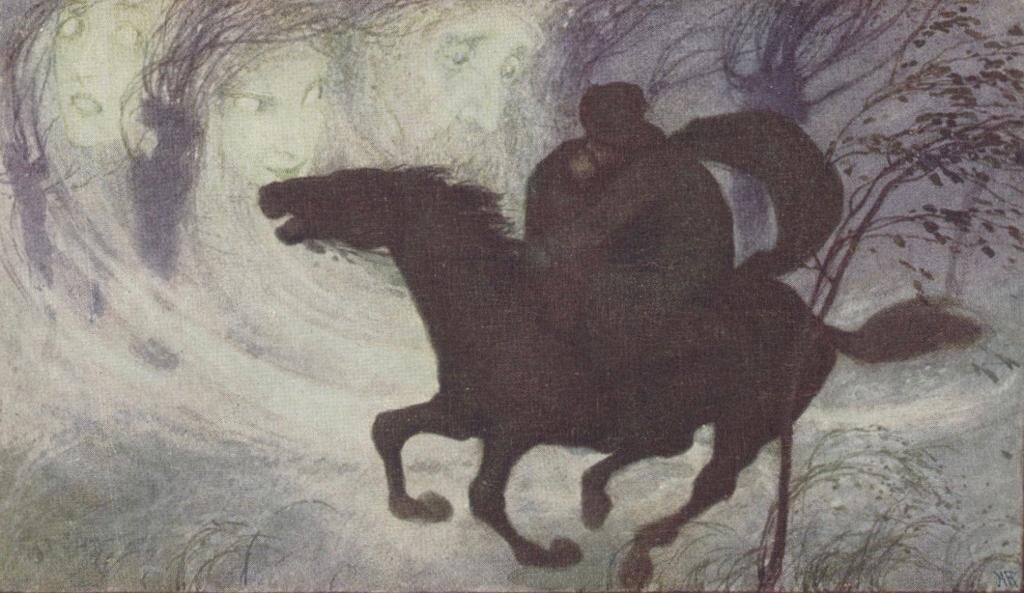

Ernst’s greatest gift to the violin repertoire is his re-creation of the horror story Der Erlkönig. This Lied transcription is spookily accurate, capturing the drama in Schubert’s score down to the smallest detail.

Liszt, another phenomenal transcriber, singled out three of Schubert’s Waltzes Nobles and Sentimentales (from the several dozen he composed for piano) and turned them into the charming Soiree du Vienne.

Paganini’s Cantabile, which emerged only after his death, has a spiritual almost hymn-like quality which seems to contrast with the fact that the church refused to bury his body for decades because of the rumours that he formed a pact with the devil (only 35 years after his death was his body finally laid to rest, with the Pope's permission). It displays the lyrical purity always present in Paganini’s works, without the technical aspect ever overshadowing his genuine musicality. The fact that several significant composers, including Brahms, Rachmaninov and Lutosławski, have taken inspiration from Paganini’s music is testament to his influence.

For this recording I couldn’t be more grateful to team up with my friend and wonderful chamber music partner, Michail Lifits. It has been exciting to go beyond virtuosity to explore the violin’s potential in different contexts of song: Lieder, Bel Canto, fantasy on song, and variations on operatic themes.